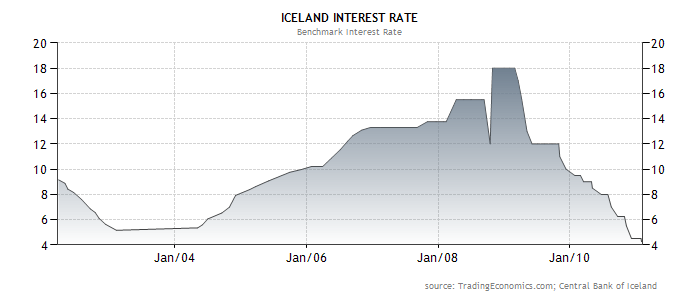

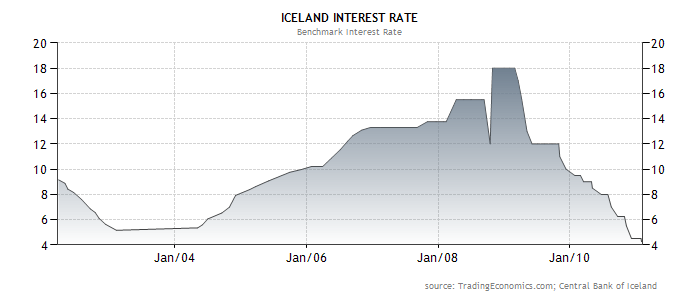

[postlink]http://breaknewsonline.blogspot.com/2011/04/icelandic-kronur-lessons-from-failed_29.html[/postlink]A little more than two years ago, the Icelandic Kronur was one of the hottest currencies in the world. Thanks to a benchmark interest rate of 18%, the Kronur had particular appeal for carry traders, who worried not about the inherent risks of such a strategy. Shortly thereafter, the Kronur (as well as Iceland’s economy and banking sector) came crashing down, and many traders were wiped out. Now that a couple of years have passed, it’s probably worth reflecting on this turn of events.

At its peak, nominal GDP was a relatively modest $20 Billion, sandwiched between Nepal and Turkmenistan in the global GDP rankings. Its population is only 300,000, its current account has been mired in persistent deficit, and its Central Bank boasts a mere $8 Billion in foreign exchange reserves. That being the case, why did investors flock to Iceland and not Turkmenistan?

The short answer to that question is interest rates. As I said, Iceland’s benchmark interest rate exceeded 18% at its peak. There are plenty of countries that offered similarly high interest rates, but Iceland was somehow perceived as being more stable. While it didn’t apply to join the European Union (its application is still pending) until last year, Iceland has always benefited from its association with Europe in general, and Scandinavia in particular. Thanks to per capita GDP of $38,000 per person, its reputation as a stable, advanced economy was not unwarranted.

On the other hand, Iceland has always struggled with high inflation, which means its interest rates were never very high in real terms. In addition, the deregulation of its financial sector opened the door for its banks to take huge risks with deposits. Basically, depositors – many from outside the country – parked their savings in Icelandic banks, which turned around and invested the money in high-yield / high-risk ventures. When the credit crisis struck, its banks were quickly wiped out, and the government chose not to follow in the footsteps of other governments and bail them out.

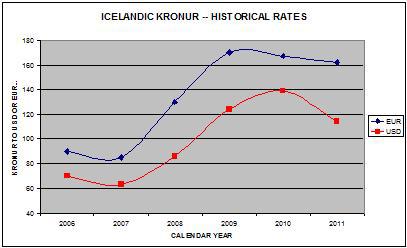

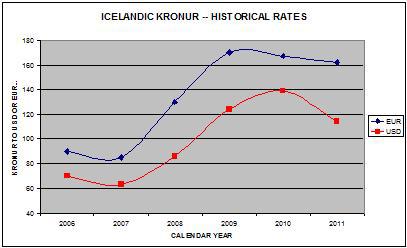

Moreover, it doesn’t look like Iceland will regain its luster any time soon. Its economy has shrunk by 40% over the last two years, and one prominent economist has estimated that it will take 7-10 years for it to fully recover. Unemployment and inflation remain high even though interest rates have been cut to 4.25% – a record low. The Kronur has lost 50% of its value against the Dollar and the Euro, the stock market has been decimated, and the recent decision to not remunerate Dutch and British insurance companies that lost money in Iceland’s crash will only serve to further spook foreign investors. In short, while the Kronur will probably recover some of its value over the next few years (aided by the possibility of joining the Euro), it probably won’t find itself on the radar screens of carry traders anytime soon.In hindsight, Iceland’s economy was an accident waiting to happen, and the global financial crisis only magnified the problem. With Iceland – as well as a dozen other currencies and securities – investors believed they had found the proverbial free lunch. After all, where else could you earn an 18% by putting money in a savings account? Never mind that inflation was just as high; with the Kronur rising, carry traders felt assured that they would make a tidy profit on any funds deposited in Iceland.

A little more than two years ago, the Icelandic Kronur was one of the hottest currencies in the world. Thanks to a benchmark interest rate of 18%, the Kronur had particular appeal for carry traders, who worried not about the inherent risks of such a strategy. Shortly thereafter, the Kronur (as well as Iceland’s economy and banking sector) came crashing down, and many traders were wiped out. Now that a couple of years have passed, it’s probably worth reflecting on this turn of events.

At its peak, nominal GDP was a relatively modest $20 Billion, sandwiched between Nepal and Turkmenistan in the global GDP rankings. Its population is only 300,000, its current account has been mired in persistent deficit, and its Central Bank boasts a mere $8 Billion in foreign exchange reserves. That being the case, why did investors flock to Iceland and not Turkmenistan?

The short answer to that question is interest rates. As I said, Iceland’s benchmark interest rate exceeded 18% at its peak. There are plenty of countries that offered similarly high interest rates, but Iceland was somehow perceived as being more stable. While it didn’t apply to join the European Union (its application is still pending) until last year, Iceland has always benefited from its association with Europe in general, and Scandinavia in particular. Thanks to per capita GDP of $38,000 per person, its reputation as a stable, advanced economy was not unwarranted.

On the other hand, Iceland has always struggled with high inflation, which means its interest rates were never very high in real terms. In addition, the deregulation of its financial sector opened the door for its banks to take huge risks with deposits. Basically, depositors – many from outside the country – parked their savings in Icelandic banks, which turned around and invested the money in high-yield / high-risk ventures. When the credit crisis struck, its banks were quickly wiped out, and the government chose not to follow in the footsteps of other governments and bail them out.

Moreover, it doesn’t look like Iceland will regain its luster any time soon. Its economy has shrunk by 40% over the last two years, and one prominent economist has estimated that it will take 7-10 years for it to fully recover. Unemployment and inflation remain high even though interest rates have been cut to 4.25% – a record low. The Kronur has lost 50% of its value against the Dollar and the Euro, the stock market has been decimated, and the recent decision to not remunerate Dutch and British insurance companies that lost money in Iceland’s crash will only serve to further spook foreign investors. In short, while the Kronur will probably recover some of its value over the next few years (aided by the possibility of joining the Euro), it probably won’t find itself on the radar screens of carry traders anytime soon.

The collapse of the Kronur, however, has shown us that the carry trade is anything but risk-free. In fact, 18% is more than what lenders to Greece and Ireland can expect to earn, which means that it is ultimately a very risky investment. In this case, the 18% that was being paid to depositors were generated by making very risky investments. As the negotiations with the insurance companies have revealed, depositors had nothing protecting them from bank failure, which is ultimately what happened.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

When you enter into a carry trade, understand that a spike in volatility could wipe out all of your profits in one session. The only way to minimize your risk is to hedge your exposure. Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

At its peak, nominal GDP was a relatively modest $20 Billion, sandwiched between Nepal and Turkmenistan in the global GDP rankings. Its population is only 300,000, its current account has been mired in persistent deficit, and its Central Bank boasts a mere $8 Billion in foreign exchange reserves. That being the case, why did investors flock to Iceland and not Turkmenistan?

The short answer to that question is interest rates. As I said, Iceland’s benchmark interest rate exceeded 18% at its peak. There are plenty of countries that offered similarly high interest rates, but Iceland was somehow perceived as being more stable. While it didn’t apply to join the European Union (its application is still pending) until last year, Iceland has always benefited from its association with Europe in general, and Scandinavia in particular. Thanks to per capita GDP of $38,000 per person, its reputation as a stable, advanced economy was not unwarranted.

On the other hand, Iceland has always struggled with high inflation, which means its interest rates were never very high in real terms. In addition, the deregulation of its financial sector opened the door for its banks to take huge risks with deposits. Basically, depositors – many from outside the country – parked their savings in Icelandic banks, which turned around and invested the money in high-yield / high-risk ventures. When the credit crisis struck, its banks were quickly wiped out, and the government chose not to follow in the footsteps of other governments and bail them out.

Moreover, it doesn’t look like Iceland will regain its luster any time soon. Its economy has shrunk by 40% over the last two years, and one prominent economist has estimated that it will take 7-10 years for it to fully recover. Unemployment and inflation remain high even though interest rates have been cut to 4.25% – a record low. The Kronur has lost 50% of its value against the Dollar and the Euro, the stock market has been decimated, and the recent decision to not remunerate Dutch and British insurance companies that lost money in Iceland’s crash will only serve to further spook foreign investors. In short, while the Kronur will probably recover some of its value over the next few years (aided by the possibility of joining the Euro), it probably won’t find itself on the radar screens of carry traders anytime soon.

The collapse of the Kronur, however, has shown us that the carry trade is anything but risk-free. In fact, 18% is more than what lenders to Greece and Ireland can expect to earn, which means that it is ultimately a very risky investment. In this case, the 18% that was being paid to depositors were generated by making very risky investments. As the negotiations with the insurance companies have revealed, depositors had nothing protecting them from bank failure, which is ultimately what happened.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

When you enter into a carry trade, understand that a spike in volatility could wipe out all of your profits in one session. The only way to minimize your risk is to hedge your exposure.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

Now that the carry trade is making a comeback, it’s probably a good time to take a step back and re-assess the risks of such a strategy. Even if Iceland proves to be an extreme case – since most countries won’t let their banks fail – traders must still acknowledge the possibility of massive currency depreciation. In other words, even if the deposits themselves are guaranteed, there is an ever-present risk that converting that deposit back into one’s home currency will result in losses. That’s especially true for a currency that is as illiquid as the Kronur (so illiquid that it took me a while to even find a reliable quote!), and is susceptible to liquidity crunches and short squeezes.

No comments:

Post a Comment